Athabasca University | AU Student/Staff Login | Invited Guest Login

- Bookmarks

- Jon Dron

- Main folder

- Motivation

- Understanding the response to financial and non-financial incentives in education: Field...

Understanding the response to financial and non-financial incentives in education: Field experimental evidence using high-stakes assessments

- Public

- 1 recommendation

Gerald Ardito recommended this November 9, 2016 - 3:26pm

What they did

This is a report by, Simon Burgess, Robert Metcalfe, and Sally Sadoff on a large scale study conducted in the UK on the effects of financial and non-financial incentives on GCSE scores (GCSEs are UK qualifications usually taken around age 16 and usually involving exams), involving over 10,000 students in 63 schools being given cash or 'non-financial incentives'. 'Non-financial incentives' did not stretch as far as a pat on the back or encouragement given by caring teachers - this was about giving tickets for appealing events. The rewards were given not for getting good results but for particular behaviours the researchers felt should be useful proxies for effective study: specifically, attendance, conduct, homework, and classwork. None of the incentives were huge rewards to those already possessing plenty of creature comforts but, for poorer students, they might have seemed substantial. Effectiveness of the intervention was measured in terminal grades. The researchers were very thorough and were very careful to observe limitations and concerns. It is as close to an experimental design as you can get in a messy real-world educational intervention, with numbers that are sufficient and diverse enough to make justifiable empirical claims about the generalizability of the results.

What they found

Rewards had little effect on average marks overall, and it made little difference whether rewards were financial or not. However, in high risk groups (poor, immigrants, etc) there was a substantial improvement in GCSE results for those given rewards, compared with the control groups.

My thoughts

The only thing that does surprise me a little is that so little effect was seen overall, but I hypothesize that the reward/punishment conditions are so extreme already among GCSE students that it made little difference to add any more to the mix. The only ones that might be affected would be those for whom the extrinsic motivation is not already strong enough. There is also a possibility that the demotivating effects for some were balanced out by the compliance effects for others: averages are incredibly dangerous things, and this study is big on averages.

What makes me sad is that there appears to be no sense of surprise or moral outrage about this basic premise in this report.

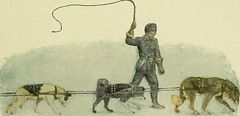

It appears reasonable at first glance: who would not want kids to be more successful in their exams? When my own kids had to do this sort of thing I would have been very keen on something that would improve their chances of success, and would be especially keen on something that appears to help to reduce systemic inequalities. But this is not about helping students to learn or improving education: this is completely and utterly about enforcing compliance and improving exam results. The fact that there might be a perceived benefit to the victims is a red herring: it's like saying that hitting dogs harder is good for the dogs because it makes them behave better than hitting them gently. The point is that we should not be hitting them at all. It's not just morally wrong, it doesn't even work very well, and only continues to work at all if you keep hitting them. It teaches students that the end matters more than the process, that learning is inherently undesirable and should only done when there is a promise of a reward or threat of punishment, and that they are not in charge of it.

It appears reasonable at first glance: who would not want kids to be more successful in their exams? When my own kids had to do this sort of thing I would have been very keen on something that would improve their chances of success, and would be especially keen on something that appears to help to reduce systemic inequalities. But this is not about helping students to learn or improving education: this is completely and utterly about enforcing compliance and improving exam results. The fact that there might be a perceived benefit to the victims is a red herring: it's like saying that hitting dogs harder is good for the dogs because it makes them behave better than hitting them gently. The point is that we should not be hitting them at all. It's not just morally wrong, it doesn't even work very well, and only continues to work at all if you keep hitting them. It teaches students that the end matters more than the process, that learning is inherently undesirable and should only done when there is a promise of a reward or threat of punishment, and that they are not in charge of it.

The inevitable result of increasing rewards (or punishments - they are functionally equivalent) is to further quench any love of learning that might be left at this point in their school careers, to reinforce harmful beliefs about how to learn, and to further put students off the subjects they might have loved under other circumstances for life. In years to come people will look back on barbaric practices like this much as we now look back at the slave trade or pre-emancipation rights for women.

Studies like this make me feel a bit sick.

- Some meandering thoughts on 'good' and 'bad' learning

December 20, 2022 - 7:39pm

Jon Dron - The importance of a good opening line

April 24, 2024 - 5:41pm

Jon Dron - Slides from my webinar, How to Be an Educational Technology: An Entangled Perspective on Teaching

September 24, 2024 - 1:00pm

Jon Dron - Preprint - The human nature of generative AIs and the technological nature of humanity:...

October 9, 2023 - 12:09pm

Jon Dron

Jon Dron

Help

Bookmarks are a great way to share web pages you have found with others (including those on this site) and to comment on them and discuss them.

Adding comments to this site

We welcome comments on public posts from members of the public. Please note, however, that all comments made on public posts must be moderated by their owners before they become visible on the site. The owner of the post (and no one else) has to do that.

If you want the full range of features and you have a login ID, log in using the links at the top of the page or at https://landing.athabascau.ca/login (logins are secure and encrypted)

Disclaimer

Posts made here are the responsibility of their owners and may not reflect the views of Athabasca University.

Comments

I totally agree.